Miriam Reiss1, Thomas Czypionka1,2

1Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS), Vienna, Austria

2London School of Economics, United Kingdom

Introduction

A widely-used definition of public health as ‘the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organised efforts of society’ was put forward by Donald Acheson in 1988 (Acheson, 1988). The broadness and ambiguity of this definition shows that it is difficult to draw a line around the services, functions and institutions which are categorised under the umbrella of public health. While this was already true before COVID-19, the pandemic has shone a spotlight on the variety of action areas to be tackled by public health agencies. This article aims to outline the roles of public health agencies and institutions in selected European countries, illustrated by their actions during the COVID-19 pandemic. The focus is on the early phases of the pandemic when countries had to rely on their pre-existing public health infrastructure.

Public health functions vary across countries

In 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) published a list of 10 essential public health operations (EPHOs) as part of their action plan for strengthening public health capacities and services (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2012). In its most recent version, the list includes (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2015):

- Surveillance of population health and well-being

- Monitoring and response to health hazards and emergencies

- Health protection, including environmental, occupational and food safety and others

- Health promotion, including action to address social determinants and health inequity

- Disease prevention, including early detection of illness

- Assuring governance for health

- Assuring a competent public health workforce

- Assuring organisational structures and financing

- Information, communication and social mobilization for health

- Advancing public health research to inform policy and practice.

However, WHO acknowledges that this list of operations is not definitive, rather what is considered to be “public health capacity and services” may change over time and may be viewed differently across countries (Rechel et al., 2018; WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2012). Furthermore, the allocation of competences and tasks across different public health agencies is closely tied to the governance structure of the health system in general. In this context, aspects like the degree of centralisation or the relative weight of the public sector compared to the private sector come into play (Rechel et al., 2018). As a result, the way the provision of public health services is organised in different countries varies greatly.

In many countries, public health functions are highly fragmented across institutions, organisations and levels of governance. This fragmentation may entail inefficiencies or even deficiencies in public health activities due to redundancies, conflicts of competence, or malfunctioning information flows. WHO has therefore explored the possibility of mergers between institutions with the aim of creating national public health agencies or institutes (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2018). Some countries, e.g. Sweden and France, have recently implemented such mergers and established central public health authorities. Moreover, while some countries traditionally attach a high value to public health and have therefore developed a strong infrastructure in this regard, others have invested only limited resources.

Examining public health agencies’ roles in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe

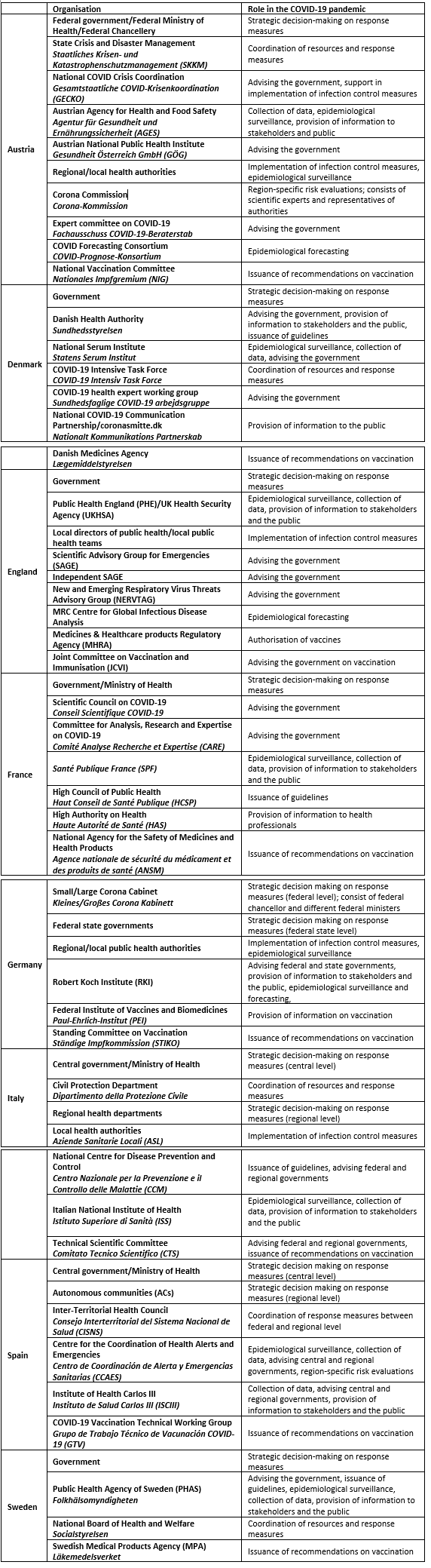

The differences in public health systems across countries have manifested in large variations in the roles played by national public health agencies in managing the crisis. Table 1 provides an overview of the relevant public health actors involved in the pandemic response in selected European countries.

Table 1. The role of organisations in the public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic in selected European countries

The French public health system has undergone several waves of reorganisation since the 1990s. Two national public health authorities, namely the High Council of Public Health (Haut Conseil de Santé Publique, HCSP) and the High Authority on Health (Haute Autorité de Santé, HAS) were created in 2004 and 2005, respectively. Further, in 2016, four former national agencies were merged into a new agency named Santé Publique France (SPF). SPF is responsible for a wide range of public-health related tasks, including collection of health data and surveillance, health promotion and disease prevention, as well as management of health emergencies including communicable diseases (Chambaud & Hernández-Quevedo, 2018).

One would expect that an organisation with such a comprehensive mandate, as well as an extensive stock of resources and expertise at its disposal, would have been the major strategic player in the French response to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, rather than relying on public health advice from these pre-existing organisations, the government set up two scientific committees in March 2020 that were mostly made up of medical experts: the Scientific Council on COVID-19 (Conseil Scientifique COVID-19) and the Committee for Analysis, Research and Expertise on COVID-19 (Comité Analyse Recherche et Expertise, CARE). While the purpose of the latter mainly consisted of making recommendations for therapeutic options, the former took on a central role in advising the government on all questions related to managing the pandemic (Rozenblum, 2021). At the same time, the role of the pre-existing public health agencies was mostly restricted to logistical and technical activities during the first months of the crisis. The tasks of SPF, for example, included implementing an epidemiological surveillance system, procuring protective equipment, organising testing logistics and publishing data (Santé Publique France, 2021). This approach of essentially side-lining established public health agencies has been attributed to the government’s desire to be in full control of the development of response measures as well as the communication of these measures to the public (Rozenblum, 2021).

England is arguably one of the countries with the strongest traditions of public health worldwide. Its public health system, however, also experienced significant restructuring with the introduction of the Health and Social Care Act in 2012. At the centre of this reform was the transferral of various public health services from National Health Service (NHS) control to local authorities and the creation of Public Health England (PHE), a national-level executive agency of the Department of Health (Middleton & Williams, 2018). In addition to creating confusion over the competences and roles of different organisations, it has been argued that the reorganisation amounted to a weakening of the previously strong public health sector, resulting in a lack of public health leadership (Scally et al., 2020). Meanwhile, PHE has already been restructured once more, forming in 2021 the UK Health Security Agency and the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities.

Similarly to the French case, the early crisis response in England was mostly guided by scientific advisory groups – most prominently, the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) – rather than established public health agencies. During the first weeks of the outbreak, the response strategy was infamously geared towards building up herd immunity, as more restrictive measures taken in other countries were widely rejected by decision makers (House of Commons Health and Social Care and Science and Technology Committees, 2021). SAGE, which is dominated by modellers and epidemiologists, played a central role in this phase. Its composition has been criticised for the lack of key disciplines like virology and public health. Moreover, there appears to have been interference from political advisors, potentially compromising the group’s independence and transparency (Middleton, 2020; Scally et al., 2020). In response to this criticism, senior experts in various fields formed a group named Independent SAGE in May 2020 as a counterpart to the government’s advisory group, which has since issued its own reports and recommendations (Middleton, 2020).

PHE took on a more operational role in the crisis, being responsible for epidemiological surveillance, data collection and information provision. Furthermore, it worked together with local directors of public health (DPHs) and their teams, who were in charge of executing response measures and managing the impacts of the pandemic on a local level (Ross et al., 2021).

Another country that took an alternative path in its management of the pandemic was Sweden. Sweden also has one key national agency for public health, the Public Health Agency of Sweden (Folkhälsomyndigheten, PHAS). It was formed in 2014 when the National Institute for Public Health (Folkhälsoinstitutet) and the Institute for Communicable Disease Control (Smittskyddsinstitutet) were merged to establish an expert government agency with a comprehensive mandate across the public health spectrum (Burström & Sagan, 2018).

In contrast to its equivalents in France and England, PHAS was the central player in devising the early national response to the COVID-19 pandemic. As an advisory agency, PHAS does not have any legislative powers so can only issue non-binding recommendations to the government. However, the Swedish government closely followed the guidance provided by PHAS, giving the agency and its experts a strong factual mandate. From the onset of the crisis, this guidance deviated significantly from the containment strategies adopted by other European countries, as it relied heavily on voluntary rather than mandatory regulations. After facing increasing criticism, the agency lost some of its influence in autumn 2020 (Pashakhanlou, 2021). The Swedish government appointed an expert commission named the Corona Commission (Coronakommissionen) in June 2020 to evaluate the country’s pandemic management. In its reports, the Commission has criticised PHAS for its late actions and lax recommendations, while also pointing to whether it was too risky a strategy to essentially leave the crisis response to one single authority (Corona Commission, 2021).

Another Nordic country, Denmark, took a very different approach than Sweden. Its most important public health authorities, the Danish Health Authority (Sundhedsstyrelsen) and the National Serum Institute (Statens Serum Insitut, SSI), were not as strongly involved in strategic activities as PHAS in Sweden, partly due to a different administrative tradition in the field of public health (Nielsen & Lindvall, 2021). Instead, they took on advisory and technical tasks, while the government devised the country’s response strategy under the strong involvement of opposition parties and relevant stakeholder organisations in an effort to find general consensus (Ornstrom, 2021).

The government also took on the leading role in Austria’s response to the pandemic. Austria traditionally does not have a particularly strong public health infrastructure, with competences and responsibilities scattered across several organisations and administrative levels. Public health operations lie predominantly with regional and local authorities or are embedded into primary care. There are virtually no institutions that are exclusively in charge of public health. Partly resulting from this low degree of institutionalisation of public health, expertise in this field is also relatively scarce in Austria (Mätzke, 2021).

In case of an epidemic, the Epidemics Act transfers most decision-making competences to the federal level. During the first weeks of the pandemic, the federal government made mostly unilateral decisions on containment measures to demonstrate their resolve and strength in crisis management. Expert advice was sought from simulation experts and a scientific advisory group of medical specialists, but there was a lack of transparency regarding upon which evidence the decisions were based (Czypionka & Reiss, 2021). The federal states, which usually have high political weight in the federalist country, as well as opposition parties, were mostly side-lined during this phase. State governments, district authorities and municipalities were, however, in charge of implementing most of the measures (e.g. test-trace-isolate) due to their broad operational competences in (public) health (Mätzke, 2021). This circumstance led to some degree of fragmentation in the implementation of response measures, which was further amplified in later stages of the pandemic when the federal states gained more political influence in crisis management. In an effort to improve coordination, a new body entitled National COVID Crisis Coordination (Gesamtstaatliche COVID-Krisenkoordination, GECKO) was established in late 2021. It consists of a broad range of experts and stakeholder representatives and is designed to advise the government and support implementation of measures.

The German “public health service” (Öffentlicher Gesundheitsdienst) is also mostly made up of regional and local authorities. Responsibilities and tasks of these approximately 400 public health offices are predominantly determined by the federal states, which hold the bulk of competences in health matters. While administration of public health is located at the regional or local level, epidemiological surveillance and research in this field are conducted at the national level. The Robert Koch Institute (RKI) is Germany’s national scientific institution in the field of biomedicine with a specialisation in communicable diseases. It was previously a part of the Federal Health Office, which was dissolved in 1994 (Plümer, 2018).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the RKI played a key role in Germany’s response to the outbreak, even though it does not have any formal authority in the pandemic response. It monitored the situation and – drawing on its extensive expertise – acted as the central advisory body to both the federal government and regional/local health authorities. The federal states and municipalities were in charge of planning and implementing response measures, but received guidelines from and engaged in constant exchange with the RKI. Several exchange forums were established for this purpose (Halm et al., 2021; Hattke & Martin, 2020). The decentralised allocation of competences, however, led to a high degree of heterogeneity in regulations across states, which were not always aligned with COVID-19 infection and death rates.

In addition to its advisory role to authorities, the RKI was also one of the main sources of information to the general public. During the first weeks of the outbreak, the team of the RKI gave daily press conferences and published numerous risk assessments, strategy documents, surveillance reports and technical guidelines, and its website served as a widely used information portal on the virus. The head of the RKI flanked the Chancellor in the government’s press statements (Czypionka & Reiss, 2021), but also issued independent advice, sometimes arguing for a change in the government’s response.

Regional authorities are central public health players in both Spain and Italy. The regions in Italy and the autonomous communities (ACs) in Spain hold almost the entirety of competences in (public) health matters. Within Spanish ACs, there is usually a general directorate responsible for planning and provision of public health services. A proposal was put forward in 2011 to create an independent public health agency at the national level to develop, coordinate and evaluate health policy, but the proposal was eventually rejected due to budgetary concerns and continued ownership of tasks by the Ministry of Health. Furthermore, in the course of austerity measures taken after the global financial crisis, many ACs were forced to impose cuts on health spending and to privatise parts of public health operations (Dubin, 2021).

The first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic hit both Spain and Italy very early and very hard when compared to the rest of Europe. In both countries, the management of the crisis was significantly hampered by a lack of coordination between central and regional governments. After initial conflicts on response measures between the ACs and the central government in Spain, a constitutional state of alarm was declared in mid-March 2020. With this, the central government formally took control of the regional health systems through the National System of Early Alert and Rapid Response (SIAPR), but operational management structures remained unchanged. Representatives of the central government and the ACs met in the Inter-Territorial Health Council (Consejo Interterritorial del Sistema Nacional de Salud, CISNS) to negotiate containment measures and, later on, the easing of these measures. While the first weeks of the outbreak were marked by arduous and often failed coordination efforts, the involved parties began to demonstrate a greater willingness to cooperate as the crisis evolved (Dubin, 2021; Peralta-Santos et al., 2021).

Italy’s public health system faced a similar situation to the Spanish one, as it was subject to spending cuts after the global financial crisis (Falkenbach & Caiani, 2021). It also does not have a single national agency dedicated to public health. Instead, regional health departments are responsible for planning and organising public health services, which are mostly provided by a network of population-based local health authorities (Aziende Sanitarie Locali, ASLs). The regional health departments have a high degree of autonomy both in political and financial terms, which is reflected in considerable regional variations with the northern regions usually exhibiting better resourced public health structures than the less affluent southern regions (Poscia et al., 2018).

When Italy was the first European country to face a severe outbreak of COVID-19, its initial response was mostly left to the regions, which led to a highly fragmented approach to containment (Peralta-Santos et al., 2021). Only several weeks after the first deaths were recorded did the federal government begin its effort to coordinate the country’s response by specifically appointing a special commissioner and an ad-hoc scientific taskforce, the Technical Scientific Committee (Comitato Tecnico Scientifico, CTS) (Falkenbach & Caiani, 2021).

Conclusion

While there has always been considerable variation in the organisation and capacity of public health agencies and services across European countries, the COVID-19 pandemic and the different approaches to managing the crisis have illustrated this variation. Structural preconditions that had grown historically and current political circumstances determined the roles played by public health agencies in combatting the outbreak. One important distinction is between operational and strategic activities: while in some countries, public health agencies decisively shaped national response strategies, in others, they only engaged in tasks like surveillance, data collection or contact tracing. It remains to be seen whether the experience gained during the crisis will lead to reforms in public health systems across Europe such as improvements in coordination, mergers across organisations or further strengthening of the public health decision-making function.

References

Acheson, D. (1988). Public Health In England: The Report Of The Committee Of Inquiry Into The Future Development Of The Public Health Function. HMSO.

Burström, B., & Sagan, A. (2018). Sweden. In Organization and financing of public health services in Europe: Country reports. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/detail.action?docID=5916242

Chambaud, L., & Hernández-Quevedo, C. (2018). France. In Organization and financing of public health services in Europe: Country reports. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/detail.action?docID=5916242

Corona Commission. (2021). Summary: Sweden in the Pandemic. https://coronakommissionen.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/summary-sweden-in-the-pandemic.pdf

Czypionka, T., & Reiss, M. (2021). Three Approaches to Handling the COVID-19 Crisis in Federal Countries: Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. In Coronavirus Politics: The Comparative Politics and Policy of COVID-19. University of Michigan Press.

https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11927713

Dubin, K. A. (2021). Spain’s Response to COVID-19. In Coronavirus Politics: The Comparative Politics and Policy of COVID-19. University of Michigan Press.

https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11927713

Falkenbach, M., & Caiani, M. (2021). Italy’s Response to COVID-19. In Coronavirus Politics: The Comparative Politics and Policy of COVID-19. University of Michigan Press.

https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11927713

Halm, A., Grote, U., an der Heiden, M., Hamouda, O., Schaade, L., & Rexroth, U. (2021). Das Lagemanagement des Robert Koch-Instituts während der COVID-19-Pandemie und der Austausch zwischen Bund und Ländern. Bundesgesundheitsblatt, Gesundheitsforschung, Gesundheitsschutz, 64(4), 418–425.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-021-03294-0

Hattke, F., & Martin, H. (2020). Collective action during the Covid-19 pandemic: The case of Germany’s fragmented authority. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 42(4), 614–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2020.1805273

House of Commons Health and Social Care and Science and Technology Committees. (2021). Coronavirus: Lessons learned to date (HC 92).

https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/7496/documents/78687/default/

Mätzke, M. (2021). Political Resonance in Austria’s Coronavirus Crisis Management. In Coronavirus Politics: The Comparative Politics and Policy of COVID-19. University of Michigan Press.

https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11927713

Middleton, J. (2020). UK’s alternative scientific advisers put public health first. BMJ, 369.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2056

Middleton, J., & Williams, G. (2018). England. In Organization and financing of public health services in Europe: Country reports. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/detail.action?docID=5916242

Nielsen, J. H., & Lindvall, J. (2021). Trust in government in Sweden and Denmark during the COVID-19 epidemic. West European Politics, 44(5–6), 1180–1204.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1909964

Ornstrom, D. (2021). Denmark’s Response to COVID-19: A Participatory Approach to Policy Innovation. In Coronavirus Politics: The Comparative Politics and Policy of COVID-19. University of Michigan Press.

https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11927713

Pashakhanlou, A. H. (2021). Sweden’s coronavirus strategy: The Public Health Agency and the sites of controversy. World Medical & Health Policy, n/a(n/a).

https://doi.org/10.1002/wmh3.449

Peralta-Santos, A., Saboga-Nunes, L., & Magalhaes, P. C. (2021). A Tale of Two Pandemics in Three Countries: Portugal, Spain, and Italy. In Coronavirus Politics: The Comparative Politics and Policy of COVID-19. University of Michigan Press.

https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11927713

Plümer, K. D. (2018). Germany. In Organization and financing of public health services in Europe: Country reports. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/detail.action?docID=5916242

Poscia, A., Silenzi, A., & Ricciardi, W. (2018). Italy. In Organization and financing of public health services in Europe: Country reports. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/detail.action?docID=5916242

Rechel, B., Maresso, A., Sagan, A., Hernández-Quevedo, C., Williams, G., Richardson, E., Jakubowski, E., & Nolte, E. (2018). Introduction. In Organization and financing of public health services in Europe: Country reports. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/detail.action?docID=5916242

Ross, S., Fenney, D., Thorstensen-Woll, C., & Buck, D. (2021). Directors of public health and the Covid-19 pandemic: A year like no other.

https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/directors-public-health-covid-19-pandemic

Rozenblum, S. D. (2021). France’s Multidimensional COVID-19 Response. Ad Hoc Committees and the Sidelining of Public Health Agencies. In Coronavirus Politics: The Comparative Politics and Policy of COVID-19. University of Michigan Press.

https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11927713

Santé Publique France. (2021). Committed to improving health for all. 2020 annual report of Santé Publique France.

Scally, G., Jacobson, B., & Abbasi, K. (2020). The UK’s public health response to covid-19. BMJ, 369, m1932.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1932

WHO Regional Office for Europe. (2012). European Action Plan for Strengthening Public Health Capacities and Services.

https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/171770/RC62wd12rev1-Eng.pdf

WHO Regional Office for Europe. (2015). Self-assessment tool for the evaluation of essential public health operations in the WHO European Region. 113.

WHO Regional Office for Europe. (2018). Establishing National Public Health Institutes through mergers—What does it take? 32.